No ocean-liner glamour or port-arrival festivity here. Ship and iceberg now merge as partners in crime, as cold-blooded killers of 1,502 civilians. The partitioning of the edifice alludes to the fracturing of the

Titanic as it sank. Each wing's upright angularity abstracts both the ship's prow and the upending of each ship-half as it plunged into the depths of the Atlantic Ocean.

The main prow gestures down the center of the contiguous slipways of the

Titanic and the

Olympic, signifying their side-by-side construction as near-twin sisters (

Titanic was 1,004 tons larger) and properly integrating the building into the original Harland & Wolff site and the

River Lagan beyond (where

Titanic first sailed) to pay homage to Belfast's maritime history.

A gesture of hope and redemption is Rowan Gillespie's

Titanica (right), a bronze diving female sculpture recalling a ship's figurehead. The organic fell swoop of her diving pose offsets the building's crystalline coldness with a remembrance of the

Titanic's faded beauty, yet blends with the wavy curves of the façade's silver-anodized aluminium shards as a conveyance of motion through the seas, of an iron will to move forward from the fall.

The wave-scaled texture of the 3,000 shards contrasts the free flow of the Atlantic's waves with the glacial stasis of the iceberg. The upward thrust of the wings suggests passengers' hapless gestures for help as the ship was sinking, and the sharp edges and corners convey the cold cutting through them like a knife as hypothermia drained their lives away.

One recalls the remark made by Captain Lord's Second Officer Herbert Stone on the bridge of the

SS Californian as he was observing the

Titanic tilting and dimming in the water, getting a first impression of her apparent distress: "Have a look at her now. She looks very queer out of the water — her lights look queer." Thus the oddly skew form of Titanic Belfast evokes the liner's loss of "unsinkable" vainglory in light of her irremediable peril.

The giant sheet of cut-out block letters spelling out her name clarifies

the building's intent to the perplexed observer of this queer sight, in an industrial way that suggests the rusting

away of a once-revered ship to bare-bones scrap iron down on the Atlantic

floor.

|

| Photo by M. Kooiman, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons |

Speaking of industrial, Harland & Wolff's landmark Samson and Goliath shipbuilding gantry cranes get their due as well. Their monumental geometry and inverted tapering are aptly integrated into the geometric cantilevers of Titanic Belfast's wings, as a testament to the shipyard's bold intention to build an ocean liner of rectitude and renown.

Look out below

|

| Photo courtesy of Titanic Belfast |

Inside, the quirky angles of the prows and cranes slash across the sea-deep atrium space as beams, catwalks, escalators and rust-finished bent panels. The cutthroat calamity of the

Titanic's fatal plunge meets the German Expressionism of the movie sets of Robert Wiene's

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Tim Burton's

Batman (1989).

|

| Photo by Leslie Shaw, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons |

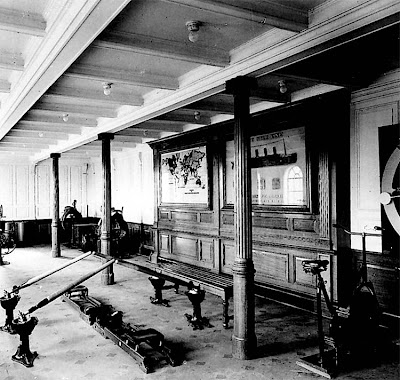

This craggy, jagged ricochet of diagonals takes us on what feels like a voyage through the catacombs of a ship's hull — or a wreck thereof — as we experience a smorgasbord of ship models, floor plans, artifacts, replicas, photos, multimedia shows and virtual tours on the

Titanic's design, construction, launch, sinkage, aftermath, legacy and rediscovery.

Ship-shape

|

| Photo courtesy of Titanic Belfast |

Contrasting the erratic deconstruction of the atrium is the prim reconstruction of the

Titanic's Grand Staircase, as

Walter Lord described it in

A Night to Remember (1955): "The setting was equally incongruous — the huge glass dome overhead ... the dignified oak paneling ... the magnificent balustrades with their wrought-iron scrollwork ... and, looking down on them all, an incredible wall clock adorned with two bronze nymphs, somehow symbolizing Honor and Glory crowning Time."

Yet this incongruous juxtaposition of ultramodern and neoclassical makes its point, as a statement of the vanity of all the vanity expressed in the ship's posh first-class interiors as they went to waste. It also goes to show how the ship's mechanical plainface scarcely prepared its first-class passengers for the surprise that awaited them inside...

The essence of the eggshell

|

| Photo by F.G.O. Stuart (1843-1923) |

The

Titanic's clean-lined shell was the kind

Le Corbusier revered for the honest, unadorned functionalism that made it a practical "machine for living" — though one of its funnels lied about its function (as did Willy Stöwer): it provided ventilation rather than exhaust emission, and was used to complete the composition of the ship. But her face fooled her passengers as well...

Knowing full well how the

Titanic's dress circle of Astors, Guggenheims, Morgans, Rothschilds, Ryersons, Strauses, Thayers and Wideners couldn't

bear the thought of

living in a machine, builder

Thomas Andrews embellished their first-class interior with

the Beaux-Arts décor of the era's finest mansions and hotels that were home to them — carved oak and French walnut paneling, wrought-iron rails, leaded glass, bronze statues, gold- plated light fixtures, crystal chandeliers, crown moldings, beamed ceilings, custom carpets, silken draperies, damask panels, marble commodes, porcelain china, sterling silverware...

|

| ...and it didn't stop at the top of the stairs... |

Lifeboat luxury

No wonder none of those nabobs wanted to get into the lifeboats as the waters were rising over their riches. Some were steadfast about the ship's imperviousness to icebergs. Others couldn't part with their proud possessions. For some, it was too cold and cramped in the lifeboats without their horsehair overcoats, mink stoles, or roaring fires in the massive lounge hearth. For others, it was beneath their dignity to be degraded from lounge to lifeboat level. Still others preferred to go down with their worldly wealth — "go down like gentlemen," as

Benjamin Guggenheim put it after dressing up for his descent — so they could die dignified rather than destitute, with hope for a higher-end heaven. After all, "In my Father's house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you." (John 14:2)

I may be resorting to the romanticism I attacked above. But it's hard not to wax romantic about this era of elegance that ended with the tanking of the

Titanic...

Sea-sheen

|

| Photo by Myk Reeve, courtesy of Wikipedia |

|

| Photo by Max Lieberman, courtesy of Wikipedia |

...and ultimately ushered in a new iron age: deconstructivist waterfront architecture of an angly, scaly, wavy sheet-metal sheen that voluptuously vivifies the waves, fish fins and ship sterns of the seaside it sits on and emphatically expresses the stormy, precarious uncertainty of the water, the weather, the wind, and the titanic technology that tests its tenacity against the torrents. Shining examples include Frank Gehry's

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Spain (1997), Schwartz/Silver Architects' 1998 expansion of the

New England Aquarium in Boston, and, of course, Titanic Belfast.

The perpetually perplexing polarity between the Titanic's architectonic advancement and technological tragedy defies artistic interpretation, often retreating it to the comfort zone of crassly palpable romanticism. Witness the sinking-ship literalism of Willy Stöwer's "Untergang der Titanic" (1912, right), the factually challenged melodrama of the two Titanic movies (1953 and 1997), and the generic sugarpop of Robin and RJ Gibb's just-premiered Titanic Requiem.

The perpetually perplexing polarity between the Titanic's architectonic advancement and technological tragedy defies artistic interpretation, often retreating it to the comfort zone of crassly palpable romanticism. Witness the sinking-ship literalism of Willy Stöwer's "Untergang der Titanic" (1912, right), the factually challenged melodrama of the two Titanic movies (1953 and 1997), and the generic sugarpop of Robin and RJ Gibb's just-premiered Titanic Requiem.

No comments:

Post a Comment